Lions are big. Tigers are bigger. Lion-tiger hybrids are biggest. Why?

- Related Topics:

- Quirky questions,

- Animal biology,

- Epigenetics,

- Gene expression,

- Comparing species

A curious adult from Colorado asks:

“Lions are big.

Tigers are bigger.

Lion-tiger hybrids are biggest.

Does this potentially indicate lions and tigers have unique genetic growth mechanisms? If the same genes controlled growth in tigers and lions, would it not follow that the hybrids would be the same size? Could hybrids be bigger because both growth genes are activated?”

The liger, a lion-tiger hybrid is bigger than both lions and tigers. How is this possible? It turns out that it’s not just your genes that matters, but who you got them from!

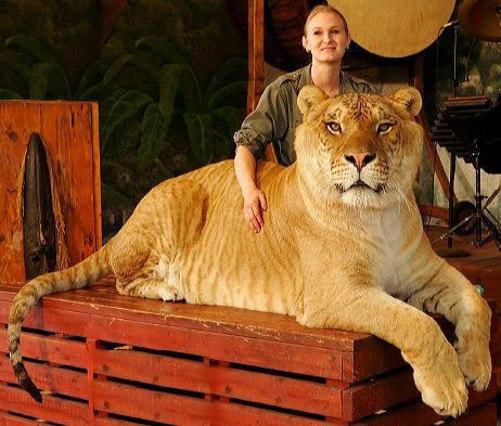

Ligers are the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion. They are the biggest of all the big cats.

Tigons are the opposite. They are the offspring of a female lion and a male tiger, and are about the same size as the average lion.

If ligers and tigons are both lion/tiger hybrids, why are they different sizes?

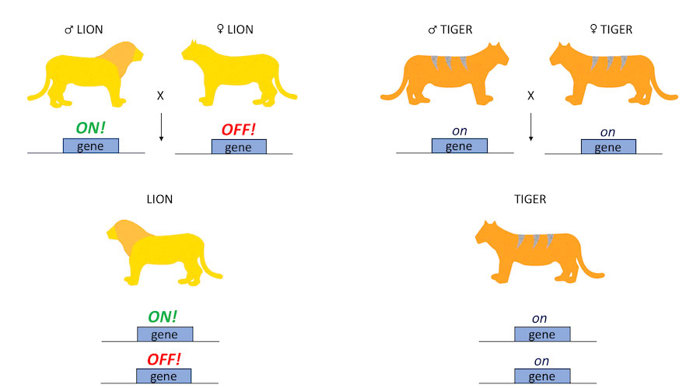

Scientists have not yet done complete genetic analyses of lion/tiger hybrids, so we don’t know the exact answer. Currently, the prevailing explanation for this difference in size is due to a phenomenon called imprinting. Imprinting is a process where the DNA in sperm and eggs are modified even before fertilization. This can switch parts of the DNA “on” and other parts “off”.

Lions and tigers imprint their DNA differently. These differences have most likely evolved due to their different lifestyles and reproductive habits.

Lion and tiger parents want different things

Lions are social and live in small groups called prides. A lioness can mate with any number of male lions in the pride... and she can have a litter with cubs from multiple fathers!

Because the cubs can have different fathers, there is an incentive for male lions to have the biggest offspring. He would want his cubs to do better than their littermates!

On the other hand, the lioness is mother to all the cubs in the litter. She wants all her babies to have an equal chance at surviving! Ideally, she wants all the offspring to be medium size so that she will have a successful pregnancy and be able to care for the cubs once they are born.

Tigers are different. Unlike lions, they are mostly solitary. Tigresses only mate with one male tiger at a time. All her cubs will have the same father.

This means the reproductive goals of male and female tigers are the same. Both want all the cubs to have an equal chance at surviving, so there is no pressure on male tigers to have large offspring.

Imprinting adds instructions to DNA sequences

But how do reproductive goals result in genetic differences? Mammals have evolved a way to pass on maternal or paternal goals to their offspring. They do this by imprinting.

DNA is like an instruction manual. But instead of having the instructions for building a chair or a table, it has the instructions to build living things, like lions and tigers.

While sperm and eggs are in the adults, prior to fertilization, their DNA can be modified. This can turn certain bits of the DNA “on” or “off”.

These modifications do not change the DNA sequence itself. It’s just like if you were building a chair and you decided to underline or cross out certain instructions in order to make the chair you want. For example, the instructions might read:

- Sand down until completely smooth and then paint pink.

You could underline certain parts to give them emphasis, such as:

- Sand down until completely smooth and then paint pink.

Or you could cross out an instruction you decided you did not want to follow, such as:

- Sand down until completely smooth and then paint pink.

You can make these modifications without changing any of the words in the manual. The process in which these types of modifications are made to the DNA in eggs or sperm is called imprinting.

What are other examples of imprinting?

One of the most well-studied cases of imprinting is in mice. Just like lions, female mice can have litters with pups from multiple fathers. Therefore, male mice want their offspring to be big, so that their pups survive best from the litter. Female mice want all their offspring to be of moderate size.

The gene “Insulin-like growth factor 2”, or Igf2, tells a developing embryo to grow. The version that is inherited from the father is underlined, telling the embryo to grow a lot. The version inherited from the mother is crossed out, telling the embryo not to grow too much.

Therefore, only the Igf2 gene inherited from the father is active. The baby mouse still gets a version from both parents, but only the one from dad is turned “on”.

Imprinting does not change the DNA letters themselves. Instead, imprinting causes methylation. Methylation is a chemical change that adds a small molecule on top of the DNA sequence. This chemical change acts like a stop sign, and turns the gene off.

Methylation near the Igf2 gene results in increased production of dad’s version of the gene compared to mom’s version.

Because lions and mice have similar mating strategies, they probably have similarly imprinting strategies. Male lions want their offspring to be big, and female lions want their offspring to be medium-sized.

A male lion’s sperm has imprinted growth genes saying “grow really big!” This usually meets a female lion’s egg that has imprinted genes saying “don’t grow too much.” This combination cancels each other out and makes an average sized lion.

But because female tigers only mate with one male at a time, male tigers don’t need to have big cubs. Tigers probably have not evolved similar imprinting strategies. Their eggs and sperm will just say “grow medium-sized.”

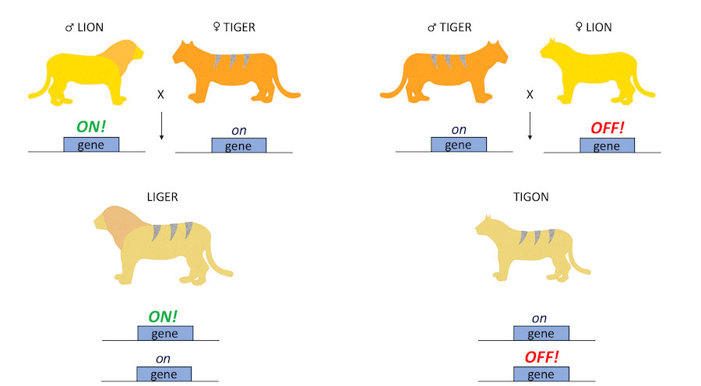

This means when a male lion’s “grow really big!” sperm combines with a female tiger’s “grow medium-sized” egg, the result is a really big liger.

This imprinting also explains why a tigon is not nearly as big. If a male tiger’s “grow medium-sized” sperm combines with a lioness’s “don’t grow too much” egg, the result is a cat that isn’t any bigger than its parents.

There haven't been very many genetic studies on lions and tigers … they’re much harder to study than mice! They take much longer to grow and are much more difficult to take care of.

Currently we do not know for sure which genes are imprinted in lions or tigers, or which of these genes make the biggest differences in terms of growth. There have been recent studies on big cats to compare genome sequences between tigers, lions and leopards. However, these studies do not give us information about imprinting.

The technology exists to find methylation sites in DNA, so maybe in the future we will uncover more about imprinting differences between lions and tigers. But for now, scientists can infer a lot about these big cats based on evolutionary theories and what we know from mice.

Author: Trisha Chong

When this answer was published in 2018, Trisha was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Developmental Biology, studying spatiotemporal protein localization in bacteria in Lucy Shapiro’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation