When was the first criminal caught using DNA evidence?

- Related Topics:

- Forensics,

- Biotechnology,

- History

A middle school student from North Carolina asks:

"When was the first criminal caught using DNA evidence?"

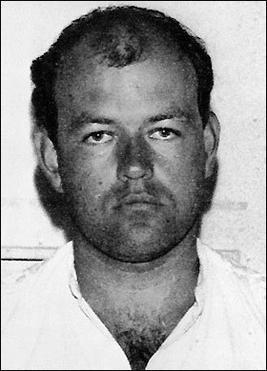

The first criminal caught using DNA was a man named Colin Pitchfork, who was arrested in 1987 for the murder of two 15 year-old girls. Read on to see how he was caught!

The case

In 1983, 15-year-old Lydia Mann disappeared on the way to a friend’s house in the village of Narborough, Leicestershire in England. She was eventually found dead, strangled by her own scarf. Three years later, in 1986, 15-year-old Dawn Ashworth disappeared while walking home. She was eventually found dead in the exact same manner. Because of the similarities in the two murders, police concluded both were committed by the same person.

Naturally, the little village was paralyzed with fear. The police acted quickly and arrested Richard Buckland, a 17 year-old boy with an intellectual disability. Buckland knew Dawn Ashworth and appeared to know some unreleased details about the crimes, making him a natural suspect. He also confessed multiple times to murdering Dawn, although he retracted his words each time. He was eventually charged with Dawn’s murder.

However, he vehemently denied murdering Lydia. The police, sure that the two crimes were related, searched for some evidence that would connect Buckland to both murders. This is where DNA comes in.

Alec Jeffreys and DNA Fingerprinting

Less than ten miles away at the University of Leicester, a professor had recently invented a new way to identify people: DNA fingerprinting. In 1985, Professor Alec Jeffreys changed the world by publishing this method, which made it possible to identify an individual by distinctive patterns in their DNA.

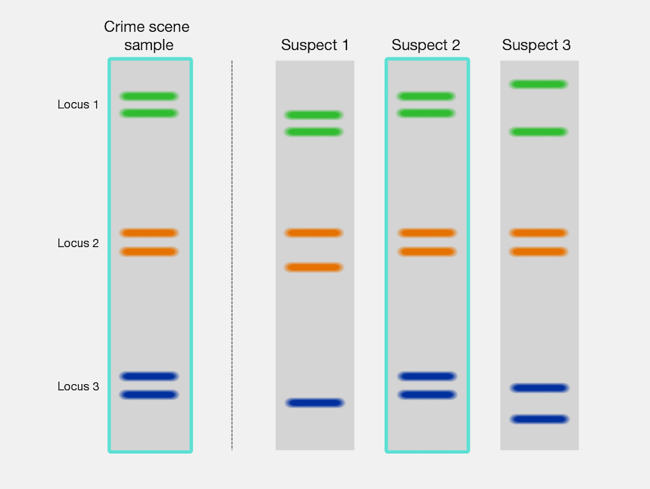

Jeffreys noticed that certain segments of DNA, called “minisatellites”, are repeated different numbers of times in different people. With enough minisatellites, one can obtain a pattern of repetition unique to each person, just like a fingerprint! To visualize this pattern, Jeffreys extracted minisatellite DNA and placed it into a gel. He then ran a current through the gel, causing the DNA to move along it. Shorter segments of DNA (ie. fewer repeats) move quickly across the gel, while longer segments (more repeats) move a shorter distance. At the end of the experiment, the DNA is visible as “bands” on the gel, meaning each person’s DNA will have a unique pattern of bands. In this way, identifying an unknown DNA sample is simple — all we have to do is match the pattern!

The first application of DNA fingerprinting did not actually come in solving crimes. Instead, Jeffreys’ method found great popularity in paternity testing for immigration cases, where it was used to determine if certain children were truly the offspring of British citizens. Indeed, when Jeffreys first suggested the use of his method in forensics, he was met with laughter from the audience.

However, they would soon be proven very wrong…

Solving the crime

Eventually, the Narborough police asked Jeffreys to perform his new DNA test on Buckland to determine if he could be linked to both deaths. Jeffreys compared Buckland’s DNA to DNA from fluids on both corpses. But his conclusion was startling: not only was Buckland cleared of Lydia Mann’s death, he was completely innocent of both murders!

The results stunned the police, who decided to conduct a mass DNA testing program of virtually every adult male in the area. However, even after the DNA of over 5,000 men was collected, no match could be found.

This line of inquiry seemed to be losing momentum. However, in August 1987, the police received a massive stroke of luck. A local man was overheard in a pub admitting that he was pressured by someone named Colin Pitchfork to impersonate him and take the police DNA test in his name. Pitchfork was arrested soon after, and when his actual DNA was tested, it was found to be a match! Pitchfork confessed to both crimes soon after. The police had their criminal.

Pitchfork, who would otherwise never have been suspected, was sentenced to a minimum of 30 years in prison. Buckland, who would have almost certainly been convicted, was released. Thus, for the first time ever, DNA testing not only identified a criminal but also set free an innocent man. Isn’t science awesome?

What’s changed today?

The story of Colin Pitchfork’s arrest serves as a strong reminder of the power of DNA analysis in the field of forensics. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that DNA profiling remains an essential part of the forensic toolkit even today. Of course, our ability to study DNA has become more effective and sophisticated over the last 30 years, meaning DNA results are cleaner and more powerful than ever before. However, the general idea remains the same as what Alec Jeffreys brilliantly identified — forensic scientists still use repeating regions of DNA to produce unique patterns for each person. This simple yet powerful concept has solved countless crimes over the past few decades, and it will surely continue to do so in the future.

Read More:

-

The Guardian: Killer breakthrough – the day DNA evidence first nailed a murderer

-

University of Leicester: The history of genetic fingerprinting

-

Arizona State: Alec John Jeffreys

-

UK Forensics Library: Colin Pitchfork

-

Golden State Killer suspect tracked down through familial DNA

Author: Aman Patel

When this article was published in 2023, Aman was a PhD candidate in the Department of Computer Science, developing Artificial Intelligence approaches to study evolution and gene regulation as part of Anshul Kundaje’s laboratory. He wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at the Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation